WHEN Emmerson Mnangagwa took over the presidency following the November 2017 coup that toppled Zimbabwe's long-time ruler Robert Mugabe, he did not waste time in telling the world that his government would adopt a political approach that diverged from that of his predecessor.

Deploying the language of "reform" as part of a well-planned strategy that was designed to mobilise Western support, the new strongman even managed to convince some rather naive diplomats into believing that he was the person with whom the West could "do business with".

However, this whole enterprise was thoroughly discredited when protesters took to the streets of Harare on August 1 to voice their displeasure at the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission (Zec)'s delay in announcing the presidential results.

In response to the demonstration, Mnangagwa panicked and dared to do the unthinkable; he deployed the military onto the streets and, within a few hours, more than six unarmed civilians had been killed.

To the international community, the massacre not only confirmed the regime's vulnerability to dramatic strategies when its hold on power is threatened, but was also a brutal reminder of the true nature of its leader - Mnangagwa - amongst several heinous crimes, Mnangagwa is allegedly responsible for the largest post-colonial massacre, known as Gukurahundi in which more than 20 000 people were killed.

And later, together with Vice-President Constantino Chiwenga, he orchestrated another hecatomb in 2008, resulting in the deaths of more than 270 opposition activists.

Understanding the West

In their relations with the other states, there is always a reliable way to tell what Western states think about others. The technique yields very well to arcane messages that might be sent by the United States, Britain or Brussels to, say, Zimbabwe, Ghana or Afghanistan. And, the method is simple: listen to what they are actually saying about other states and their leaders using a "Straussian" approach.

Named after German political philosopher Leo Strauss, the "Straussian" reading encourages the reader or listener to look out for hidden meanings in a document or rhetoric. Often, one might need to undertake some background reading on the author or speaker or subject to understand the message.

Western condemnation

Indeed, a series of statements that were put out by Washington, London, Paris and Brussels, either individually or collectively, provide significant insights on the extent the West questions the soundness of the Zanu-PF regime's claims to legitimacy. The condemnations demonstrate a crisis of faith and distrust not only on the election process that installed Mnangagwa, but also in his sincerity when he talks about reforms.

In its condemnation, the US, via its Harare embassy, was "deeply concerned" with the shootings, urging the regime to exercise restraint in dealing with protesters. Also, the European Union (EU) ambassador condemned the massacre as "serious human violations".

Even those who had been attempting to make nice with the regime, had no choice but condemn Mnangagwa. Indeed, the shootings appear to have sapped the British ambassador, Catriona Laing's energy in supporting the regime when she criticised its "excessive use of force" against protesters. She even called for the government to withdraw troops from the streets of Harare.

To demonstrate the seriousness of the matter, as if not enough, on August 7, the EU, US, Canada and Switzerland issued a joint statement: "The eruption of violence … 'stand(s) in sharp contrast to the high hopes and expectations for a peaceful, inclusive, transparent and credible election." It looked like the little impetus that the international community had for co-operation with the regime was quickly disappearing.

Diplomatic ambiguity

In other words, through those condemnations, Mnangagwa was being told in a very restrained manner that his behaviour on August 1 had rendered him illegitimate. But, it appears it was a message that did not register with the regime's officials, and the president himself.

The president's response to the condemnations demonstrates that he is not a good listener. Instead of showing that he understood the message, Mnangagwa went on to set up a widely ridiculed commission of inquiry, which many, on the basis of its composition and terms of reference, was simply an attempt to make the shootings irrelevant.

And, the reason for this poor understanding of the communication from the West is not necessarily difficult to understand: in theory, the main function of an international or foreign ministry, using various experts, is to help a government understand deeply, other states' intentions and behaviours using a "Straussian'' approach, as one of the methods. When these statements were issued out by Western states, one would have expected tens of well-qualified young international relations professionals to have been assigned to work, day and night, on the messages as they attempt to decipher the exact meanings of those carefully worded statements from the international community.

Yet in the Zimbabwean government, there are no such experts, but a few unqualified and usually relations of the regime's officials manning this important ministry. Because they lack the necessary training, knowledge and expertise, these political appointees often struggle to understand diplomatic language. For example, in its dealings with Zimbabwe, the British in particular, use language that is characterised by what is called "diplomatic ambiguity". This style in itself is telling in terms of the extent to which London is sceptical, if not dismissive of the regime's talk of reforms.

What is diplomatic ambiguity? It is the practice of being cautious by using mostly vague language about certain aspects of foreign policy or intended actions. Diplomatic ambiguity allows flexibility in a government's response and reduces the risk of damaging credibility by not adhering to a specific course of action.

Consequently, a diplomat might say what they do not necessarily mean. As my favourite English playwright, Alan Bennett, aptly puts it about his countrymen, and by extension, fellow Westerners: "The English (Westerners) are adept at saying one thing and doing the other."

Hence, as Christopher Hitchens, the late American-English journalist, warned us, any message that originates from London always requires a ''Machiaevellian'' or a "Straussian'' read. In other words, when they say we might re-engage, they might actually be meaning the opposite. One should not take what is said diplomatically at face value.

But, that is exactly what the regime has done: literally taken, the messages coming from Europe and North America: that any condemnation that falls short of calling them "illegitimate" meant that the business of governance should proceed as usual. What escapes the regime is that through these condemnations, the West has used a circuitous route to advise Mnangagwa's regime that it is indeed illegitimate.

No investment

Nothing demonstrates how the West regards Mnangagwa as illegitimate more than its reluctance to invest in Zimbabwe. The new Finance minister, Mthuli Ncube, using his global connections, has made some aggressive attempts at advertising the country to international investors.

However, the response has been discouraging. Continued visits to Western capitals and calls for investment by the minister betrays ignorance and a fundamental lack of appreciation of how the international political economy functions and how the regime's illegitimacy is at the heart of this reluctance to invest in Zimbabwe.

Sanctions

Another telling demonstration of how the West views Mnangagwa has been its reluctance to remove sanctions against his person, and that of his regime.

Indeed, the US tightening of sanctions - by setting tougher conditions for re-egagement - through the Zimbabwe Democracy and Economic Recovery Act (Zidera) is indicative of how Washington is contemptuous of the notion of a "Second Republic".

In diplomatic circles, it is understood that the US has made it clear that Mnangagwa is illegitimate, and does not want him and the Zanu-PF regime in power. Campaigns denouncing the so-called new dispensation by Washington's foreign affairs experts on social media is telling. On the other hand, the EU and Britain seem to have decided to maintain, at least for now, the sanctions against Mnangagwa, which is an indictment of how they view his regime.

International press

The international press, notably, the Washington Post and The New York Times in the US, and in the United Kingdom, The Economist and Financial Times - what I regard as UK's establishment papers - and The Guardian have been unrelenting in their attacks on the regime. These broadsheets pretty much represent the liberal constituency of the American and British populations in general.

Equally worrying is the trend that has been shaping up in the British press that has traditionally supported the Conservative Party (notably the tabloid Daily Mail and The Telegraph). The two have been scathing in their attacks on Mnangagwa, particularly after the shootings. Until recently - before the shootings - these newspapers made some half-hearted attempts at painting Mnangagwa as a reformist.

Other news outlets, in mainland Europe, have jumped onto the bandwagon in criticising Mnangagwa's regime. The press in the US and Europe shape the opinion of the voters who, in turn, influence politicians' foreign policy preferences.

International observers

But what must have been the particularly disappointing for Mnangagwa's government must have been the reports from international election observers. Mnangagwa's post-coup rulership was predicated on presenting a "clean electoral" process. However, this script was damned by international observer reports which found several irregularities, concluding that, as a result, the election fell short of standards required to call it free, fair and credible.

The joint IRI/NDI report concluded that the; "the election was fraught with many irregularities". Again, those who consult Strauss in understanding subliminal messages will not need to tell you that in these reports the Americans were politely telling Mnangagwa that he is ''illegitimate'.'

The EU's observer mission reports on the elections amplified the understanding of Mnangagwa's regime as illegitimate. By asserting that the electoral results lacked "traceablity, transparency and verifiability" and concluding that "the election fell short of international standards", the report put closure to claims of Mnangagwa as understood as legitimate by the West.

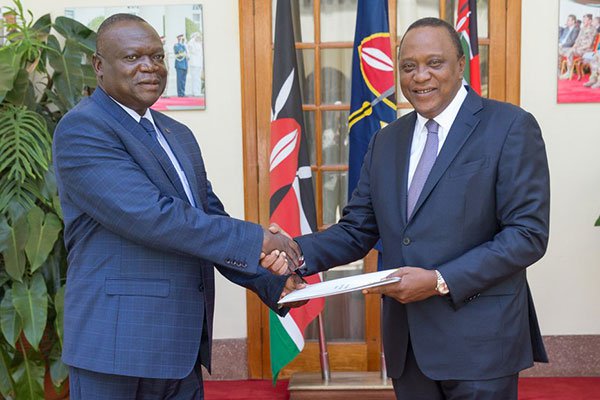

With the expectation of rejoining the Commonwealth soon, the language contained in the Commonwealth observer group on Zimbabwe was also not the one that the regime wanted to hear. The London-based group appeared all too happy to condemn the July 30 electoral outcome. Citing the same incongruous manner in which Mnangagwa claimed victory - various irregularities and the post election violence - the chair of the group, former Ghanaian president Dramani Mahama, concluded that "for these reasons, we are unable to endorse all aspects of the process as credible, inclusive and peaceful".

Unwanted in the West

When Laing was UK ambassador, the regime was falsely made to believe that in post-Mugabe Zimbabwe, Britain, and by extension, the EU's foreign policy on the Southern African nation was premised on Mnangagwa being the centre-stage. This resulted in confusing Laing's misleading activist agenda with Britain and the West's foreign policy on Zimbabwe. In other words, the "Catrional Laing-centred approach" to understanding the West's intentions on Zimbabwe was misguided.

To illustrate the perfunctory nature of British foreign policy towards Zimbabwe, when she departed for her new mission, Laing appeared to take a swipe at Mnangagwa when she condemned the pre-election playing field as "not completely level". It was a remarkable shift, and indeed a strong warning to Harare that re-engagement with Britain, EU and the US was not coming anytime soon.

Unfortunately, until the regime has heard the word "illegimate'', it is business as usual. But, the West's experience with Mugabe has taught them to avoid the inflammatory repercussions associated with calling an unpredictable regime illegitimate.

Simukai Tinhu is a Zimbabwean political scientist.

- the independent

Concern over Masvingo black market

Concern over Masvingo black market  Kenya declares three days of mourning for Mugabe

Kenya declares three days of mourning for Mugabe  UK's Boris Johnson quits over Brexit stretegy

UK's Boris Johnson quits over Brexit stretegy  SecZim licences VFEX

SecZim licences VFEX  Zimbabwe abandons debt relief initiative

Zimbabwe abandons debt relief initiative  European Investment Bank warms up to Zimbabwe

European Investment Bank warms up to Zimbabwe  Young Investment Professional (YIP) Graduate Programme 2019

Young Investment Professional (YIP) Graduate Programme 2019

Young Investment Professional (YIP) Graduate Programme 2019

Young Investment Professional (YIP) Graduate Programme 2019

Editor's Pick